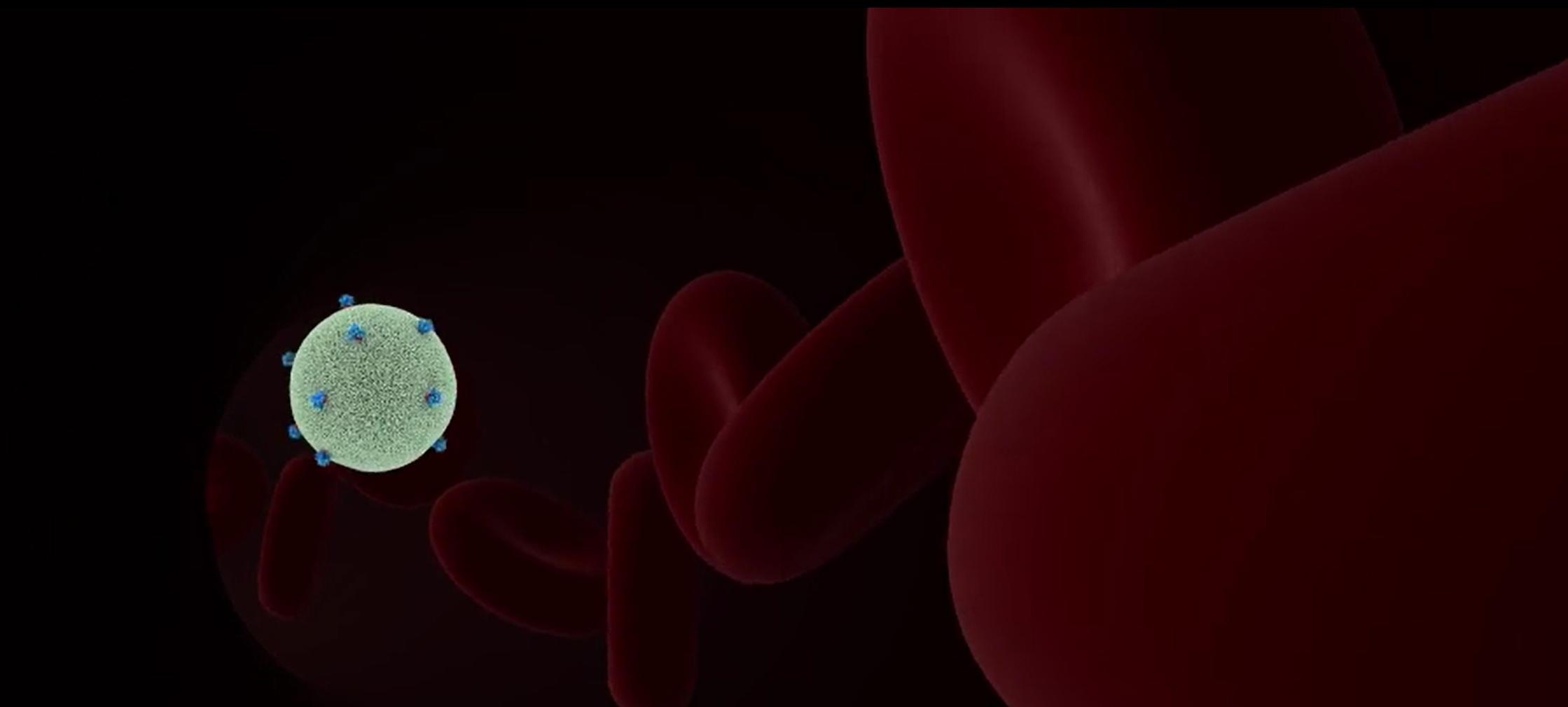

Latently Infected T-Cells

A major challenge to curing HIV is the virus’ ability to “hide” undetected in cells — a stage referred to as latency. During the HIV life cycle, HIV integrates itself into its host cell’s DNA. There it persists even when it is not being actively transcribed to make new viruses. These latent viruses can stay dormant for many years.

Antiretroviral therapies can stop new viruses that might be produced from infecting new cells but can’t eliminate viral DNA from the host cell’s genome. Some of these HIV-infected cells are long-lived CD4 memory T cells and serve as the HIV reservoirs. During the homeostatic proliferation of these memory T cells, the pool of latent HIV also gets copied.

When HIV-positive individuals are on combination antiretroviral therapy (cART), they can live relatively normal and healthy lives without developing AIDS. cART also decreases the risk of HIV transmission. However, cART requires lifelong adherence to these medications.

Management of HIV/AIDS is achieved using combinations of antiretroviral drugs. There are numerous classes of drugs that target different aspects of the HIV life cycle, and therapy always involves taking two or more classes of drugs in combination.

The most commonly prescribed drugs include those that prevent the viral genome from being copied and incorporated into the cell’s DNA. Other drugs prevent the virus from maturing, or block viral fusion, causing HIV to be unable to infect new cells in the body.

Antiretroviral therapy is highly effective at managing the levels of HIV. Continued use has been shown to keep HIV-infected individuals from ever progressing to AIDS, and can lower the viral count to nearly undetectable levels. With antiretroviral therapy, most people can expect to live long and healthy lives.

Unfortunately, antiretroviral therapy is not a cure for HIV. This is due to HIV’s ability to hide its instructions inside of cells where drugs cannot reach it.

During the HIV life cycle, HIV incorporates itself into its host cell’s DNA. Antiretroviral therapies can stop new viruses that might be produced from infecting new cells, but can’t eliminate the viral DNA from the host cell’s genome.

Most host cells will be killed by infection or will eventually die of old age, but a very small number of cells appear to live for a very long time in the body. Every so often, the viral DNA can get turned on, and the cell starts to produce new virus. This is why medication adherence is critical. Stopping medication, even for a short time, might result in new cells being infected with HIV.

Researchers are working hard to find a true cure for HIV that could completely eradicate the virus from an infected person. Current directions include finding a means to activate cells that are harboring viral DNA, forcing them “out into the open” where they can then be targeted by antiretroviral drugs. Researchers are also looking into ways of using genetic tools to delete viral DNA from the cell’s DNA.

-

Abdel-Mohsen M, Richman D, Siliciano RF, et al. Recommendations for measuring HIV reservoir size in cure-directed clinical trials. Nat Med. 2020;26(9):1339-1350. doi:10.1038/s41591-020-1022-1

Deeks SG, Lewin SR, Ross AL, et al. International AIDS Society global scientific strategy: towards an HIV cure 2016. Nat Med. 2016;22(8):839-850. doi:10.1038/nm.4108

Latency-Reversing Agents (LRA)

Latency-reversing agents are used to try to eliminate HIV reservoirs. This strategy attempts to flush the virus out of the resting cells by reawakening dormant viral DNA in the latent reservoirs. This approach is usually accompanied by a second step which aims to effectively clear the infected cells.

The most common class of latency-reversing agents are HDAC (histone deacetylase) inhibitors, which can force latently infected cells to produce viruses. Histones, which are proteins that DNA wraps around, can regulate what genes are actively transcribed. In some regions of the genome, chromatin (that is, DNA and its associated proteins) is tightly condensed. As a result, DNA in these regions are not available for the cell’s transcription machinery (such as DNA polymerase II, or Pol II), to read and copy, and thus they are not active. This is thought to be a major mechanism by which HIV can lie dormant in cells. Histone deacetylase inhibitors act to relax the chromatin and can thus enable genes on that segment of DNA to be turned on.

Some latency-reversing agents are known to produce significant toxicity and must be administered at low doses. Scientists are currently researching new LRA drugs that are both safe and effective.

-

Deeks SG, Lewin SR, Ross AL, et al. International AIDS Society global scientific strategy: towards an HIV cure 2016. Nat Med. 2016;22(8):839-850. doi:10.1038/nm.4108

Verdone L, Agricola E, Caserta M, Di Mauro E. Histone acetylation in gene regulation. Brief Funct Genomic Proteomic. 2006;5(3):209-221. doi:10.1093/bfgp/ell028