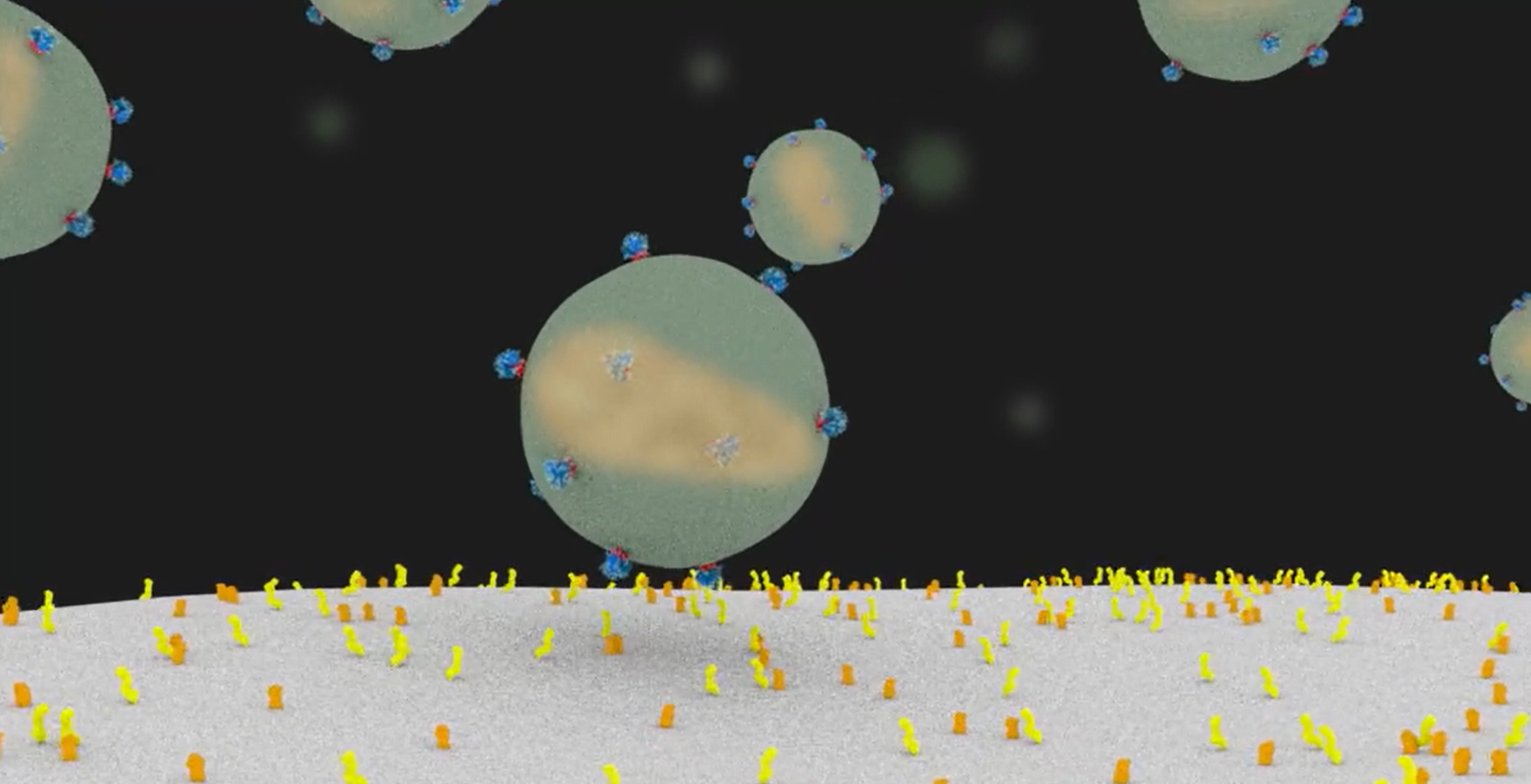

Helper T cells play a critical role in our immune systems, helping us fend off infections from bacteria and fungi. They are also the host cell for HIV, and the loss of these important cells can lead to AIDS.

The small green dot to the left of the T cell is a HIV particle, shown to scale

About HIV

Approximately 35 million people in the world are currently infected with HIV/AIDS, including over 3 million children. Each year, an additional 2 million people are newly infected with the virus. In the United States, over 1 million people are HIV-infected, and it is estimated that one in six are not aware that they are carrying HIV.

HIV infection can occur when an HIV virus reaches the mucosal membranes or the bloodstream of an individual. The virus is able to recognize and infect certain types of immune cells, particularly targeting cells known as helper T cells, or CD4+ T cells. Helper T cells play a crucial role in defending the body against bacterial and fungal infections.

During the first stage of HIV infection, called the acute infection stage, large amounts of virus are produced in helper T cells, destroying many of these cells in the process.

People often report having flu-like symptoms, such as fever, sore throat, and body aches, in addition to a skin rash during this early stage of infection. Eventually, levels of the virus and helper T cells stabilize, and the infected individual experiences fewer symptoms.

Within a few months after the initial infection, viral loads are generally low and can remain at low levels for years, even without treatment.

Over time, however, the amount of virus increases, and the levels of helper T cells decrease. When the T cell count drops low enough, individuals are much more prone to opportunistic infection. This stage of HIV infection is known as AIDS.

Animation created by Shaza Abdelrasoul (HCI PathMakers Scholar 2024)

-

Craigie R, Bushman FD. HIV DNA integration. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2012 Jul;2(7):a006890. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006890. PMID: 22762018; PMCID: PMC3385939.

Sundquist WI, Kräusslich HG. HIV-1 assembly, budding, and maturation. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2012 Jul;2(7):a006924. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006924.

Wilen CB, Tilton JC, Doms RW. HIV: cell binding and entry. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2012 Aug 1;2(8):a006866. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006866. PMID: 22908191; PMCID: PMC3405824.

Illustration created by Janet Iwasa; Updates done by Trish Luu & Rachel Torrez

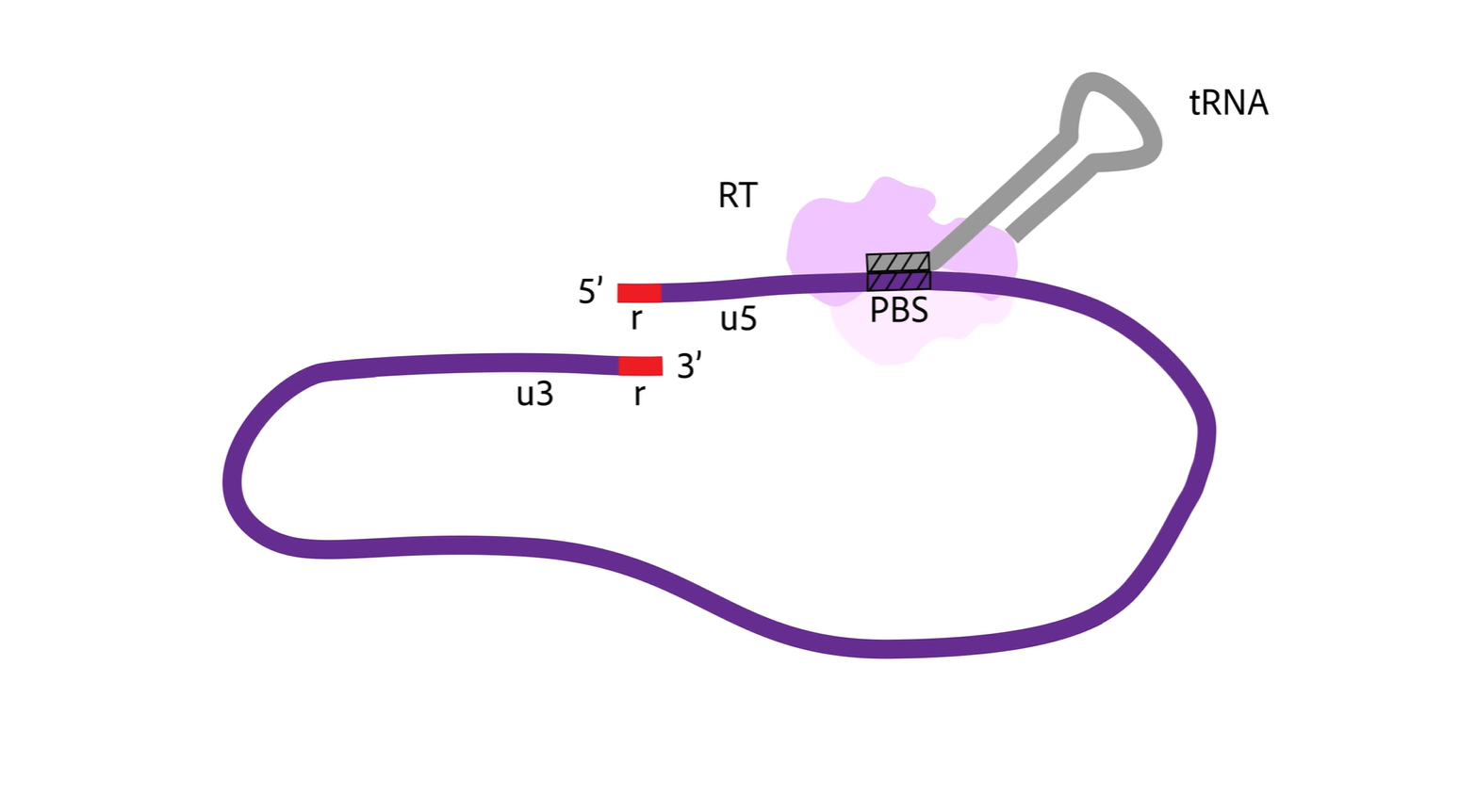

Detailed Look at Reverse Transcription

Info on RT

-

Craigie R, Bushman FD. HIV DNA integration. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2012 Jul;2(7):a006890. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006890. PMID: 22762018; PMCID: PMC3385939.

Sundquist WI, Kräusslich HG. HIV-1 assembly, budding, and maturation. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2012 Jul;2(7):a006924. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006924.

Wilen CB, Tilton JC, Doms RW. HIV: cell binding and entry. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2012 Aug 1;2(8):a006866. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006866. PMID: 22908191; PMCID: PMC3405824.

How does HIV infection occur? The following molecular animation depicts the process of how HIV infects a T cell and transforms the cell into a viral factory.

Please note that the animation shown here is a work-in-progress, and will be further updated, refined and augmented over the coming years. Additional animations will illustrate how antiretroviral drugs impact the life cycle, and how innate immunity can block HIV infection.

Click here to view a version of this animation without narration.

Download the HIV Life Cycle animation (narrated version, 523 MB)

Download the HIV Life Cycle animation (music-only version, 523 MB)

Credits:

Animated and narrated by Janet Iwasa (Department of Biochemistry, University of Utah)

Updates to reverse transcription and integration steps by Grace Hsu

Music written and performed by Joshua Roman

Music recorded by Jesse Lewis (Immersive Music Project)